It’s an Antibiotic-Resistant World

Bacteria all over the globe are evolving tricks to survive humanity’s arsenal of antibiotics, and the World Health Organization has officially sounded the alarm.

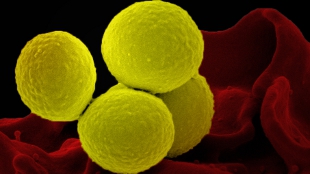

MRSA being engulfed by a human neutrophil NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ALLERGY AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES

The antibacterial resistance crisis is upon us, and unless scientists can think of ways to stave it off tout de suite, people all over the world are in a heap of trouble, according to a new report released by the World Health Organization (WHO). “A post antibiotic-era—in which common infections and minor injuries can kill—far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century,” wrote Keiji Fukuda, WHO’s assistant director-general for Health Security, in a forward to the report, the first that the organization has released concerning antibiotic resistance.

The WHO report compiles data from 114 countries, developed and developing alike. A suite of infectious bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia, and Neisseria gonorrhea, have evolved drug resistance, according to the report. In general, the rising tide of drug-resistant bugs can be blamed on the overuse of existing antibiotics, careless use and prescribing, the use of antibiotics in animal agriculture, and the failure to develop new classes of antibiotics.

“Despite the fact we've known the potential of this going cataclysmic for 10 years, as a global unit we haven't managed to get our act together,” Timothy Walsh, a medical microbiologist at Cardiff University, U.K., and adviser for the report, told Nature. Particularly worrying, Walsh continued, is the growing trend of resistance to carbapenems, a class of antibiotics that is usually reserved as a last resort to treat stubborn infections.

The report calls for the establishment of a global monitoring network to better track antibiotic resistance as it spreads around the globe.

Meanwhile, Chinese researchers reported on April 17 in Environmental Science and Technology Letters that some industrial solvents may help bacteria share an antibiotic resistance gene. So-called “ionic liquids” are usually touted as safer substitutes for volatile organic solvents, which can release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in household solutions, such as furniture polishes, paint stripper, and air fresheners. Daqing Mao, an environmental engineer at Tianjin University in China, and his colleagues found that one ionic liquid, 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate (which doesn’t release VOCs), increased by 500 times the abundance of a gene that makes bacteria resistant to the antibiotic sulfonamide. “I would never have guessed that ionic liquids stimulate antibiotic resistance,” Amy Pruden, an environmental engineer at Virginia Tech that wasn’t involved with the stidy, told Chemical & Engineering News. “It’s ideal to look at these issues before we start using ionic liquids widely.”

As if all that weren’t bad enough, scientists at the University of Manchester published a paper on Tuesday (April 29) in Nature Communications that showed bacteria in smaller congregations were more likely to mutate and become drug-resistant than were bacteria assembled in larger groups. Lead authors Chris Knight and Rok Krašovec from the University of Manchester found that E. coli in smaller groups more rapidly developed resistance to rifampicin, an antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis, than did bacteria in big colonies. But the phenomenon may extend to other bacteria and other drugs. “What we were looking for was a connection between the environment and the ability of bacteria to develop the resistance to antibiotics,” Knight and Krašovec said in a statement. “We discovered that the rate at which E. coli mutates depends upon how many ‘friends’ it has around. It seems that more lonely organisms are more likely to mutate.”